The Open/Close Principle is Confusing and, well, Wrong (SOLID is not solid)

November 14, 2019 📬 Get My Weekly Newsletter ☞

As mentioned in the original post, I’m realizing that the SOLID principles are not as…solid as it would seem. The first post outlined the problems I see with the Single Responsibility Principle, but now I’d like to talk about the most confusing of the five, the Open/Closed Principle.

This principle states that software should be “open for extension, but closed for modification”. I find this summary extremely confusing and when I dug deeper I found a whole lot of bad advice. You should ignore this principle entirely. Let’s see why.

What The Open/Closed Principle Means

This principle (as it is understood by SOLID) was developed by Robert Martin1 in a paper he wrote, based on Bertrand Meyer’s statements in the book Object-Oriented Software Construction.

Martin paraphrases Meyer thusly:

Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

He then defines “open for extension” as a module that can be made to “behave in new and different ways as the requirements of the application change, or to meet the needs of new applications”. He defines “closed for modification” as when “no one is allowed to make source code changes to it”.

Huh? This seems exactly backwards.

Adding un-needed flexibility to code (to make it open for extension) breeds complexity and carrying cost. It requires imagining all sorts of use-cases that don’t exist in order to make it ultimately flexible. This wastes time, creates more complex and complicated code, and requires that you maintain, in perpetuity, all this flexibility that you don’t need.

This is not nearly as odd as the notion that you cannot change the source code. How are we to fix bugs if we cannot change the code? Delete it and start over? This part of the principle is so seemingly wrong that it makes me question my own perception of reality.

Digging into the paper, it appears to be making the statement that classes should depend on abstract base classes, so that you can swap out the implementations of a particular class without affecting the consumers of that class. And since this is a principle, my interpretation is that you should always do this.

It’s bad advice. Flexibility is almost never needed and almost always creates more problems than it solves. It can also make it hard to understand the system’s behavior.

Flexibility is Expensive

All things being equal, code that is more flexible is more difficult to build, test, and maintain. Building features into your code that you don’t need is extra work. Based on the concept of carrying costs alone, the work required to make a class “open for extension” should be avoided. If you don’t need flexibility, don’t build it.

One of those carrying costs is the ability to understand the system’s behavior. Highly flexible code creates a lot of code paths to navigate, and the type of flexibility demonstrated in the paper—added abstract base classes—makes those code paths hard to discover.

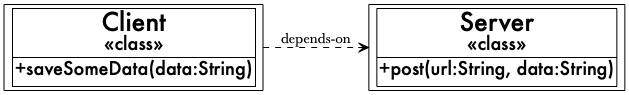

Let’s see what we’re talking about. The paper shows an example of a Client that depends on a Server:

Client and Server relationship from the paper (Bigger version in new window)

Here’s what that code might look like in Java (Ruby makes it hard to see this because Ruby has no type annotations):

public class Client {

private Server server;

public Client() {

this.server = new Server();

}

public void saveSomeData(String data) {

this.server.post("/foo", data);

}

}

public class Server {

public void post(String url, String data) {

// ....

}

}

According to the Open/Closed Principle, this class is not open for extension, since we always use a concrete

Server instance, and it is also not closed for modification, because if we wish to change to another type of server, we must change the source code.

It is not a foregone conclusion that we need to make those changes. It is also not clear that if we do, in fact, need flexibility, then this class is where that flexibility must be added.

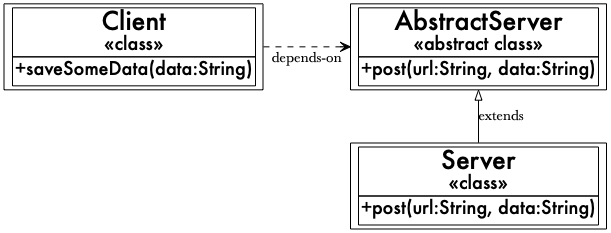

Nevertheless, this is what the paper (and thus the principle) says is how we should address this issue. We should

introduce an abstract base class for our server implementation and have Client depend on that instead.

Client, AbstractServer, and Server relationship from the paper (Bigger version in new window)

In Java, this looks like so:

public abstract class AbstractServer {

abstract void post(String url, String data);

}

public class Server extends AbstractServer {

public void post(String url, String data) {

// ....

}

}

public class Client {

public Client(AbstractServer server) {

this.server = server;

}

}

Then, whenever we create Client instances, we pass in the concrete implementation:

Client client = new Client(new Server())

Client is now open for extension, since we can pass an alternate implementation of AbstractServer into it, and it’s closed for modification because we don’t have to change the source in order to do that.

While this is a more flexible design, is it better? I don’t think it is definitely better. If we never need

more than one Server, then we have added un-needed features to our code, and we must now maintain that. It may

seem trivial in this example, but imagine an entire codebase built like this. I have worked on one, and it was

not pleasant. Writing code for it required the extra step of making abstract base classes (or interfaces) when

none were needed.

But it also made it really hard to explain and predict the system’s behavior.

Understanding System Behavior is Paramount

As programmers we must frequently explain and understand the system’s actual behavior. We must diagnose and fix bugs, explain to others what happened in the system, or make changes to add features.

In the first implementation—which violates the Open/Closed Principle—it’s pretty easy to explain the system’s

behavior because it’s not flexible. Client always uses a Server, so the path through the code is clear.

In the second implementation, however, it’s more difficult. Assuming we don’t know if Server is the only

implementation of AbstractServer, to understand the system’s observed behavior, we have to track down all uses

of Client to figure out which AbstractServer implementation was used, and then figure out which path through

the code used which one.

Imagine doing that to find that there is only one implementation of AbstractServer.

When you design your classes to be more flexible than the system needs them to be, you create complexity. When programmers add flexibility that they think they might need, the idea is to save time later by adding flexibility now. But you just don’t always know what sort of flexibility you need. To make the system truly flexible, it should implement only what it needs to and be well-tested.

My advice: Ignore the Open/Close Principle entirely. Write code to solve the problems you have.

As we examine the remaining SOLID principles, we’ll see a recurring theme of adding flexibility when none is needed, all in the name of…well…I’m not sure.

Next up is the Liskov Substitution Principle.