A Framework for Product Design Beyond the Happy Path

August 15, 2022 📬 Get My Weekly Newsletter ☞

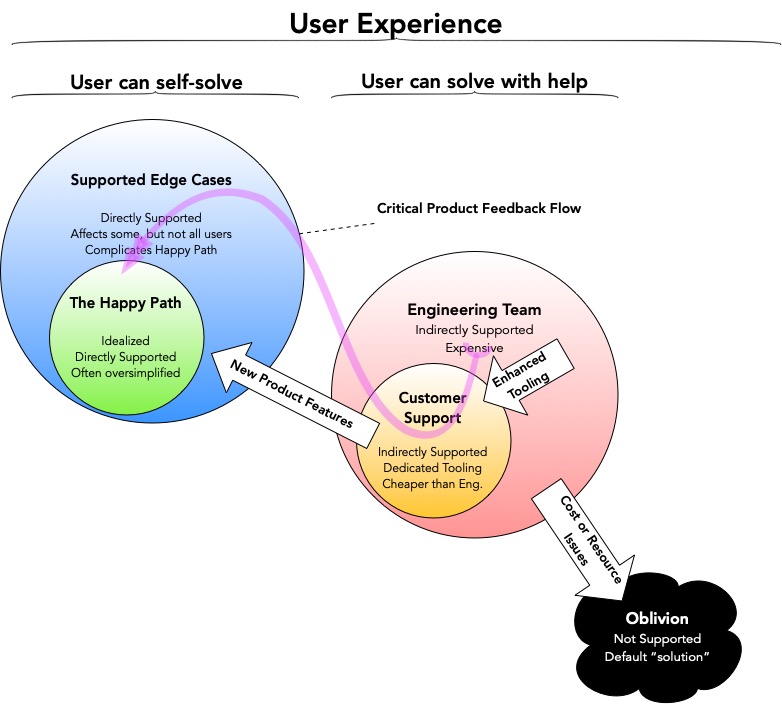

Product design—really all of design—is about how the user’s problem is solved. It’s about how it works, not how it looks. Each problem gets addressed in one of five ways: direct support via the happy path, a supported edge case, the customer support team, the engineering team, or oblivion (where it is not actually solved).

Inexperienced designers focus entirely on the happy path, whereas most product designers focus only additionally on edge cases. Even then, the lack of involvement from engineering and customer support can leave the design woefully under-developed.

This post outlines a slightly structured model for thinking through a product design inclusive of the entire user experience, including customer support.

Each problem a user needs to solve is either an intended problem that is motivating the creation of the software, an unintended problem that’s still possible to solve, or something that simply cannot be done.

Being explicit about this is critical to product design. During the early days at Stitch Fix, we had no dedicated product design team, which forced a cross functional group to collaborate. This group included engineering and customer support, which meant we could discuss the entire user experience, all the way to getting an engineer to fix something.

The result was that any user problem—no matter how insignificant or unusual—had a way to be solved, and the team had a way to push solutions from the engineering team, through customer support, to the user, based on a feedback cycle of solving problems in any way we could.

User problems can be understood in the following framework (also shown in the diagram below):

- The Happy Path is what the software exists to do. This is what everyone thinks of as the primary function of the software or feature.

- Edge Cases are less common needs that must be accounted for in the user-facing design. They inform the design.

- Customer Support handles edge cases that can’t or won’t be included in the user-facing design. Customer support often has specialized tooling to handle this, which must often be built alongside the user-facing software.

- The Engineering Team solves problems customer support cannot, since they have special access to the underlying data stores and source code.

- And when engineering can’t handle something that customer support can’t handle because there is no user-facing design for some edge case, the user’s problem ends up in oblivion, never to be addressed.

Feedback from each step feeds the steps before it to help inform roadmaps and staffing.

Inexperienced product teams focus only on the happy path. More experienced teams will make sure the design team is handling edge cases, but great teams make sure customer support is empowered to solve problems the software can’t—or shouldn’t—handle directly. Leaving solutions to the engineering team is expensive, and oblivion is where customer satisfaction goes to die.

The Happy Path is The Easy Part

It’s always great to start with the idealized use case for the product. How should it behave if there were no oddball edge cases or users with unusual demands? This is the happy path because seeing it should make users happy to see their main problem being solved for them.

Inexperienced designers and developers tend to overfocus here. This is problematic because a) the real difficulty in product design lies in edge cases, and b) users don’t care about fancy user experiences as much as designers might think. User experience is rarely the primary driver of software sales, and the true value a user derives is from the entire experience. The happy path is only a small part of that experience.

The way to drive toward a great end to end experience starts with supported edge cases.

Handling Edge Cases is for Great Software

An edge cases is anything that isn’t the primary problem the software solves, but still something that must be handled by the software itself and not delegated to customer support and beyond.

Some edge cases, such as updating a user’s data or arranging special pricing, don’t have to be supported by the user-facing software. Choosing to do this—or not—is a design decision. But other edge cases, such as the front-end losing network connectivity to the back-end, have to be handled or the software looks broken.

At Stitch Fix, one of our most commonly used internal applications was also used in an environment with terrible internet connectivity. Simply assuming the user would refresh their browser was not sufficient. The software had to handle the case where the network was slow or temporarily offline. This edge case not only informed the product design, but even the choice of technical implementation!

The bulk of the design work should be around edge cases. The reason is that the happy path design can create edge cases that need to be handled. This must inform the happy path design. It’s entirely possible to design an amazing happy path that cannot handle necessary edge cases.

An extremely common example is when a system must show data to the user. Designers often allocate what they believe is a sufficient amount of space for the largest amount of data reasonably expected. Users, however, find a way to provide more data.

How will the design accommodate this? Should the extra information be cropped, shown in a tool tip, or do we need an entirely new experience to handle this edge case? This is the hard part about design and great designers can find a solution to these problems.

Some edge cases, however, are either too difficult to design for, or affect too few users to spend time designing and building up front. But, the user experience can be preserved by ensuring that customer support can handle these cases.

Customer Support: a Product Designer’s Secret Weapon

We’ve all had to contact customer support at one time or another. Depending on the situation, and depending on the company, this might be painful or it might be quick and easy. A good product design includes customer support and even specifies changes to the customer support tooling to account for it.

For example, an app might not want to allow you to change your email once you’ve signed up. The team might feel this isn’t going to happen often and the design and coding required to support it would necessitate additional security checks and validations. They way the team can get away with not supporting it is to build a way for the customer support team to.

Unlike users, customer support is trusted to manipulate at least some internal data. Further, a user is likely to reach out via email, and customer support can easily verify their identity as well as their new email. It is likely that building a customer support interface for this is far easier—and has a far lower carrying cost—than allowing the user to do it.

Of course, the customer support team has to be a part of this design decision - they will take on the carrying cost of solving the user’s problem, so they need to have input into how this will work.

In a healthy organization, the customer support team can provide feedback on how often features like this get used. This can feed a product roadmap and can easily justify that addition of the feature later.

Sadly, the customer support experience and tooling is often the most lacking from product designs. You can tell when you contact a company. If the support agent can quickly solve what seems to be a pretty basic problem, they have good tooling and likely someone somewhere in the org made sure the user’s needs could be met through customer support.

If, however, you are waiting on the phone for a long time, or the agent has to constantly put you on hold, it’s likely the tooling available to the customer support team is lacking features needed to address common issues.

That said, even changes to customer support tooling have opportunity and carrying costs. For an extremely unlikely edge case—especially one that is complicated to support—allowing the engineering team to handle it is the right course of action.

The Engineering Team Is the Last Resort

The engineering team is more trusted than customer support—possibly the most trusted in the organization—since they have access to the underlying data stores as well as the source code. They can make changes to solve user problems that no one else can.

It may seem extremely expensive to have the engineering team do what is essentially customer support, but this can be a worthwhile trade-off. If a specific problem is complicated to solve, but happens infrequently, the carrying cost of a customer support- or user-facing solution might be higher than the cost of having an engineer handle the problem.

Having engineering be involved in support also provides them with a valuable signal about user behavior. Sometimes, a user request uncovers a bug that, when fixed, eliminates the need to build a new feature. Or, user requests can help prioritize customer service tooling enhancements that may be hard to otherwise justify.

This only works when the team is empowered to place this sort of work ahead of new features. Engineering—and customer support—need to be able to use the feedback they are getting to affect their roadmap. If not, both teams can become fatigued, and user problems end up where they will never be solved: oblivion.

Oblivion for When the Customer is Not Always Right

Some problems simply can’t be solved. Some user problems could be solved, but the team explicitly doesn’t want to support that. And, sometimes, the team dynamics and staffing mean that solvable problems get dropped. Either way, oblivion is where unsolved problems end up.

This isn’t necessarily all bad. A team can be tightly focused when everyone agrees on what problesm the team simply isn’t in the business of solving. And a roadmap or backlog can be much more easily built when there is objective data about solvable, supported problems being dropped due to understaffing or mismanagement.

Product marketing can also be more tightly focused when everyone knows what the system won’t do, or at least won’t do right now. Sometimes it’s more important to know what a product doesn’t do than what it does.

This is a Team Framework, not a Design Framework

This framework works best when product design, engineering, and customer support all work together. Only the combined group can correctly identify edge cases in the happy path and agree on how to support user needs that the software won’t support. The customer service team knows the burden each new process creates, and this can inform the design team: perhaps they do need to support an esoteric edge case because customer support can’t handle it.

This framework also works when there is no explicit product design team. You may only have a visual designer driving the design, or you might only have engineering! This framework builds alignment and provides a way to ensure the user experience is as good as it can be without building everything they could ever need right from the start.