ExplcitlyTypedSelfReferences

The Gist

Explicitly Typed Self References is, no offense, incomprehensible. However, with some help from the Scala Book, and some coding, I think I might get what to use it for.

My Interpretation

There’s two main use-cases for this feature, the first is to hold a reference to an enclosing class when this. is ambiguous (that is, ambiguous to you, the programmer, not to the compiler). The second is to allow a different type of composition of objects than would be allowed by inheritance.

Disambiguating this.

In Java, when an inner class needs to refer to its enclosing class, there are rules regarding how symbols are interpreted. Scala has similar rules. When an inner class and its enclosing class have the same symbol in scope, there is a question on how to refer to the enclosing class’ symbol from the inner class. Consider a dialog that contains a customer extension of another UI component:

Here, label inside LoginButton refers to its label and not the label of the login dialog. In Java, to explicitly reference the correct label, you would use LoginDialog.this.label. This works in Scala as well, however it has some disadvantages.

Aside from being a lot of typing, it also requires duplicating the class name of the enclosing class, which affects the maintainability of this code. Scala provides an alternative:

The line self => establishes the symbol self as a reference to the instance of LoginDialog that encloses the instance of LoginButton, thus providing a cleaner way of accessing it. self could be anything, though using “self” is considered idiomatic (despite, in my opinion, being extremely confusing).

Alternative to Inheritance

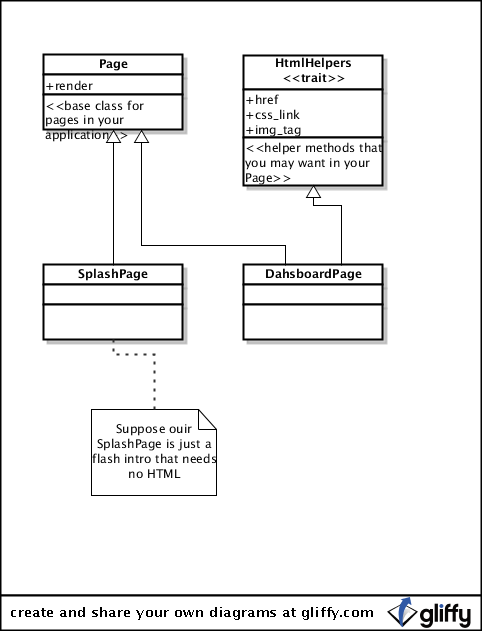

One use of ScalaTraits is to better organize your code; you can logically group code that has separate concerns in different traits. At times, however, you will always use certain traits together. Consider a very simple web application framework design:

Here we have a Page that represents a web page we’ll render, and we have a trait called HtmlHelpers which contains some useful helper methods.

Suppose that our web framework wants to take advantage of some popular CSS layout frameworks, like Blueprint. There’s a couple of obvious ways to do this. We could subclass HtmlHelpers to add Blueprint-specific helpers (and create additional subclasses for other CSS frameworks we wished to support). Or, we could create another trait for the Blueprint-specific helpers only.

Both of these choices are less than optimal; in the first case (subclassing), we end up with a somewhat strange design; BlueprintHelpers doesn’t sound like a subclass of HtmlHelpers and this creates a class hierarchy where one doesn’t naturally exist.

In the second case, we have our concerns nicely separated, but there’s a problem: BlueprintHelpers cannot access the HtmlHelpers methods.

Faced with these choices, we could just go with the subclassing method, but Scala allows a third alternative. We can tell Scala that whenever BlueprintHelpers is mixed-in, the programmer must also mix-in HtmlHelpers.

this: HtmlHelpers => is what makes this connection. This means that the code inside BlueprintHelpers can behave as if it were an instance of HtmlHelpers. If you were to mix in BlueprintHelpers and not HtmlHelpers, you would get a compile error.

My Thoughts on this Feature

This is a very weird feature. The tour entry for this is horrendous, and only after some real toying around could I come up with anything resembling a real example that didn’t require a delicate balance of knowledge of the entire Scala programming language to understand.

You might even think that this feature is not a good solution to the proposed problem. I’m not 100% convinced that it is, but I do think that the class hierarchy is a bit stronger than if we had simply subclassed HtmlHelpers. It results in classes like class AboutPage extends Page with HtmlHelpers with BlueprintHelpers which, while a bit verbose, is very clear and readable.

So, by having your classes designed in this fashion (and taking advantage of self-typing when you need to, instead of subclassing), you end up with many fine-grained classes and class definitions that are very readable. This seems more elegant to me than the Ruby way of using “macros”.